See if you can figure out why [Krugman will not like these figures]:

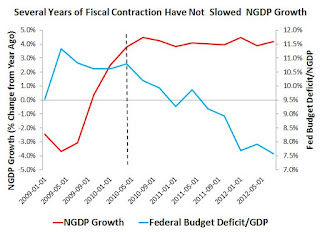

This first figure shows that aggregate demand growth has not been affected by a tightening of fiscal policy since 2010. Specifically, it shows that nominal GDP (NGDP) growth has been remarkably stable since about mid-2010 despite a contraction in federal government expenditures. The same story emerges if we look at the budget deficit relative to NGDP growth:

Both figures seriously undermine the argument for coutercyclical fiscal policy and suggest a very a low fiscal multiplier. They also indicate that the Fed has been doing a remarkable job keeping NGDP growth stable around 4.5%. Monetary policy, in other words, appears to be dominating fiscal policy in terms of stabilizing aggregate demand growth.

Beckworth's conclusion is not necessarily valid, and illustrates the danger in drawing conclusions about structural variables from looking at correlations between macroeconomic aggregates. Here's why the conclusion might not be valid:

Suppose that Keynesian demand management policy works perfectly: in other words, fiscal stimulus perfectly smooths fluctuations in aggregate demand. In that case, you will observe substantial swings in fiscal policy, but no swings whatsoever in aggregate demand. When external shocks push AD up, fiscal tightening will push it back down; when external shocks push AD down, fiscal policy will push it back up.

Beckworth's graphs give no measure of external shocks; hence, they are perfectly consistent with the idea that fiscal stimulus was allowed to wind down as the economy naturally recovered. (Tyler points this out.)

Check out Nick Rowe for an exploration of this idea in much greater depth. Using these graphs to conclude that fiscal policy is ineffective is like saying "Hey, no matter how much power my neighbor's heating system puts out from day to day, his room stays the same temperature; his heater must be useless!" It might be true. Or it might be the exact opposite of true.

Also, note that if fiscal policy is effective (i.e. if the multiplier is high), then aggregate demand will depend not just on current deficits but on expectations of the response of deficits to future external AD shocks. This is a central tenet of the "market monetarism" that Beckworth espouses, but there's no reason that forward-looking expectations can't be applied to fiscal policy as well as monetary policy.

To conclude: The graphs Beckworth shows are perfectly consistent with a large fiscal multiplier. In fact, they are perfectly consistent with the hypothesis that monetary policy is essentially ineffective, that the Fed is basically powerless, and that fiscal policy is capable of doing a perfect job of smoothing NGDP growth all on its own.

Now, I'm not saying Beckworth is wrong, and that the multiplier is big. I'm saying that the graphs he shows do not tell us much about the size of the multiplier. We should always beware of drawing conclusions about structural variables from looking at correlations between macroeconomic aggregates.

Update: David Beckworth responds (in the comments, and in an update to his post):

Noah, the thermostat assumes policy can respond in real time to the shocks. Do you really think fiscal policy is nimble enough to do this? It is reasonable to claim monetary policy can given its flexibility, but it's a stretch with fiscal policy (unless there are large automatic stabilizers built into place).Well, it's possible that there just weren't any big shocks in recent years...stimulus might have just calmly would down as planned, while the economy slowly recovered as expected. Also, remember expectations. Expectations are certainly nimble enough to respond quickly to any shock.

A bigger problem with your alternative story is that it doesn't fit the facts. Fiscal policy has been tightening despite the spate of negative economic shocks over the past few years: Eurozone crisis, debt cliff talks 2011, China slowdown which have kept U.S. economy from having a robust recovery.Well, these are certainly putative negative shocks. They seem like things that might have been shocks. But do we know that they really were shocks? The Eurozone crisis was resolved, the debt cliff talks resulted in compromise, and China's slowdown was not really that big of a deal. Maybe in reality this was small potatoes compared to the basic restorative forces, pushing us to a slow but steady recovery after the Great Recession.

Paul Krugman has made this abundantly clear in many pieces where he repeatedly laments the lack of adequate fiscal policy. Surely he wouldn't be saying this is he thought along the lines of your thermostat example?Ah, but what does Krugman consider a satisfactory outcome? The "recovery" from the Great Recession has seen pre-crisis RGDP (and NGDP) growth rates restored, but at a lower level than the pre-crisis trend; Krugman might just be dissatisfied with this outcome, even if it was the outcome produced by fiscal policy. Remember, Krugman doesn't set fiscal policy, he just talks about it a lot.

I continue to conclude that the notion that fiscal policy is ineffective is not supported by these graphs.

Update 2: Scott Sumner weighs in:

I was asked to comment on Noah Smith’s recent critique of David Beckworth’s post on the fiscal multiplier. I basically agree with Noah, and would simply add that his arguments also suggests that the standard arguments in favor of the effectiveness of fiscal stimulus are also mostly flawed, in basically the same way that he claims Beckworth’s arguments are flawed (ignoring expectations channels, etc.) When it comes to fiscal stimulus it’s all about faith—the data tell us almost nothing.The whole world seems to be converging on the idea that macro data doesn't really reveal the true workings of the macroeconomy...I personally think we can do much better, data-wise, than some simple graphs of macroeconomic aggregates, but it is true that any empirical study of the fiscal multiplier (or the money multiplier, or any such policy effect) is going to have to rely on a theoretical model which itself can't easily be verified with data...

Update 3: This blogger put up some similar graphs comparing monetary aggregates and NGDP. Guess what? Monetary aggregates jump all over the place, NGDP just sails along. Exactly like deficits and NGDP in Beckworth's graphs. There's a lesson here...

Update 4: Paul Krugman weighs in, agreeing about the graphs in question, but saying that I'm too "nihilistic" about how much we can learn from macro data. But this, dear readers, is a topic for another post...

No comments:

Post a Comment