In studying screenwriting, I'm struck time and again by how many tricks of good screenwriting can be carried over to traditional fiction writing (stories, novels, novellas), often to the great benefit of the latter.

A common complaint about bad screenplays is that they're a lot of work to read, because the author spends too much time in flowery descriptive narrative. You can tell when you're reading one of these scripts: It takes you two minutes—instead of 30 or 40 seconds—to get through a page. (Once you've read some really fine scripts, and felt their rhythm, you can sense the snail-like rhythm of a "stinker" script instantly.)

In the screenwriting world, we say that bogged-down scripts often lack verticality. (Charles Deemer gives an excellent summary in his post on "Making Scripts Vertical.") The idea comes down to this: Your eye spends an awful lot of time, in a slow-moving piece of writing, simply going from left to right (LTR), parsing word by word through one sentence after another after another. (Obviously I'm talking about English and other alphabetic/LTR languages.) This is what one might call horizontality; it's the basis of all alphabetic-LTR writing, because letters and words occur sequentially. But every once in a while, your eye gets to drop down vertically on the page—when there's a new paragraph, a subhead, a section break, a new chapter heading, an inserted block quote, a bulleted list, etc. Anything that makes your eye drop down is verticality.

Your brain keeps track of the ratio of verticality to horizontality. It begins to ache after a while if there's not enough verticality.

Horizontality is tiring. Why? Because it's linear, and that's not how cognition works. Processing linear text requires a highly specialized area of the brain. Perception (involving the senses of the body in conjunction with the whole brain) results from experiences taken in episodically, not always in a particular order, as a collage of disjoint bits that may include memories, ideas, emotions, smells, sounds, what have you.

Many of the great art movements of the early twentieth century can be understood in the context of an escape from the shackles of linearity. A photo, like a reaistic painting, maps one area of light or dark (in the photo) to a similar area in the subject; in fact the verb "map" implies linearity of just this sort. Impressionism attempts to break from linearity so as to allow the brain to do what it does best: assemble meaning from disjoint bits. Likewise, a common stylistic trope of postmodern fiction is the telling of a tale as a pastiche of disconnected and not always time-ordered pieces. This sort of storytelling (think The English Patient) engages the brain in a different way than straight narrative, often to stunning effect, since nonlinear processing centers of the brain are enlisted in the attempt to render the overall meaning.

If you have any doubt as to how hard (cognitively speaking) linear, horizontal writing is for the brain, try reading the scroll version of Kerouac's On the Road (available in the 50th anniversary edition from Viking/Penguin), the version that reflects Kerouac's original rendering of the story as a single long paragraph. Somewhere around ten pages into the 300-page-long paragraph, you'll be wishing for an indent, a section break, or some other "break" from linearity. The single-long-paragraph device takes getting used to.

Screenplays are intrinsically highly verticalized. They're broken up into short pieces that vary a great deal in terms of indents and margins. Thus they tend to be much easier to read quickly than a novel. But (as I said earlier) even among screenplays, there are those that read easily and those that feel like work.

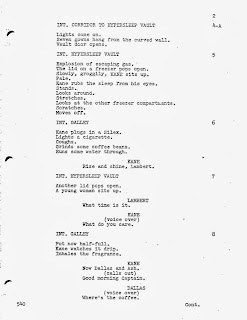

Take, for example, the following bit of narrative, adapted from Alien:

In your novel (you know, that one you've been working on all month?), before you get too tied up in Proustian 900-word sentences and Pynchonesque paragraphs that ramble on for pages, have a regard for the cognitive load imposed by linearity. Consider introducing a little more verticality.

Lighten the load.

Your reader will thank you.

reade more...

A common complaint about bad screenplays is that they're a lot of work to read, because the author spends too much time in flowery descriptive narrative. You can tell when you're reading one of these scripts: It takes you two minutes—instead of 30 or 40 seconds—to get through a page. (Once you've read some really fine scripts, and felt their rhythm, you can sense the snail-like rhythm of a "stinker" script instantly.)

|

| Page 2 of the Alien script (shooting version). |

In the screenwriting world, we say that bogged-down scripts often lack verticality. (Charles Deemer gives an excellent summary in his post on "Making Scripts Vertical.") The idea comes down to this: Your eye spends an awful lot of time, in a slow-moving piece of writing, simply going from left to right (LTR), parsing word by word through one sentence after another after another. (Obviously I'm talking about English and other alphabetic/LTR languages.) This is what one might call horizontality; it's the basis of all alphabetic-LTR writing, because letters and words occur sequentially. But every once in a while, your eye gets to drop down vertically on the page—when there's a new paragraph, a subhead, a section break, a new chapter heading, an inserted block quote, a bulleted list, etc. Anything that makes your eye drop down is verticality.

Your brain keeps track of the ratio of verticality to horizontality. It begins to ache after a while if there's not enough verticality.

Horizontality is tiring. Why? Because it's linear, and that's not how cognition works. Processing linear text requires a highly specialized area of the brain. Perception (involving the senses of the body in conjunction with the whole brain) results from experiences taken in episodically, not always in a particular order, as a collage of disjoint bits that may include memories, ideas, emotions, smells, sounds, what have you.

Many of the great art movements of the early twentieth century can be understood in the context of an escape from the shackles of linearity. A photo, like a reaistic painting, maps one area of light or dark (in the photo) to a similar area in the subject; in fact the verb "map" implies linearity of just this sort. Impressionism attempts to break from linearity so as to allow the brain to do what it does best: assemble meaning from disjoint bits. Likewise, a common stylistic trope of postmodern fiction is the telling of a tale as a pastiche of disconnected and not always time-ordered pieces. This sort of storytelling (think The English Patient) engages the brain in a different way than straight narrative, often to stunning effect, since nonlinear processing centers of the brain are enlisted in the attempt to render the overall meaning.

If you have any doubt as to how hard (cognitively speaking) linear, horizontal writing is for the brain, try reading the scroll version of Kerouac's On the Road (available in the 50th anniversary edition from Viking/Penguin), the version that reflects Kerouac's original rendering of the story as a single long paragraph. Somewhere around ten pages into the 300-page-long paragraph, you'll be wishing for an indent, a section break, or some other "break" from linearity. The single-long-paragraph device takes getting used to.

Screenplays are intrinsically highly verticalized. They're broken up into short pieces that vary a great deal in terms of indents and margins. Thus they tend to be much easier to read quickly than a novel. But (as I said earlier) even among screenplays, there are those that read easily and those that feel like work.

Take, for example, the following bit of narrative, adapted from Alien:

Dallas, Kane and Lambert, each wearing gloves, boots, and jackets, enter the air lock. All three are carrying laser pistols. As Kane touches a button, a servo begins to whine and the inner door quietly slides shut; then the trio pull on their helmets.That's not how the scene appears in the final version of the script (written by Walter Hill and David Giler, based on an earlier screenplay by Dan O'Bannon). Here's how the script was written:

Dallas, Kane and Lambert enter the lock.Telegraphic; staccato; almost poem-like. The "before" version is what you'd read in a novel (or a not-so-great screenplay). The second version, from the Hill-Giler script, is experiential, sensory in its telling. Two entirely different ways of handling the same content; two ways for the brain to process the information.

All wear gloves, boots, jackets.

Carry laser pistols.

Kane touches a button.

Servo-whine.

Then the inner door slides quietly shut.

The trio pull on their helmets.

In your novel (you know, that one you've been working on all month?), before you get too tied up in Proustian 900-word sentences and Pynchonesque paragraphs that ramble on for pages, have a regard for the cognitive load imposed by linearity. Consider introducing a little more verticality.

Lighten the load.

Your reader will thank you.