Thomas McCarthy's offbeat, low-budget (under $500,000) drama, The Station Agent, is a bit of an enigma. The 2003 film won numerous awards (critics and judges lavished praise on it), 90% of people on rottentomatoes.com liked it (average rating 3.9/5), and yet I didn't find it to be all that magical; I give it three stars, tops. Does it exude charm? Most definitely. Are the performances good? Hell yes, they're better than good. (So is the cinematography.) But somehow, long portions of the movie seemed to drag; the funny parts weren't laugh-out-loud funny; the plot was threadbare; my thoughts wandered as I watched. I wanted to come away laughing or crying or moved in some way. But it's not that kind of story.

What kind of story is it? The logline is suitably quirky: Two loners (Joe and Olivia) try to befriend an antisocial dwarf (Finbar McBride, sensitively played by Peter Dinklage) who has inherited an abandoned train station in Newfoundland, New Jersey.

Bitter and reclusive, tired of living the wee life in a world of Big People, four-foot-five-inch Finbar moves into the ramshackle station, making it his own special locomotive-geek bachelor pad. But he can't get away from the young Cuban-American man, Joe (played by Bobby Cannavale), who operates a hot dog truck near the abandoned station. (We're never told how it is a person can make a living operating a lunch truck at an abandoned station where no train ever stops.)

While walking to town, Finbar almost gets struck by a swerving Jeep; he thus meets Olivia Harris (played by Patricia Clarkson), a thirty-something woman who lost her only child in a playground accident two years ago and is now separated from her husband.

For a while, it seems as if Fin and Olivia will hit it off and become An Item, but they never do. Instead, she wants to reconcile with her husband (but finds out much later that he's already impregnated his girlfriend). Fin also meets a young librarian, and has a tender moment with her; but alas, she's pregnant by her redneck boyfriend, and she goes back to him (or disappears from the film, at least).

There's a bit of bonding between Fin and Joe, but frankly the Joe character is mostly an irritation (to Fin and the moviegoer) and only barely attains "true friend" status at the end of the story. He's good-natured; you want to like him; but he's extraordinarily immature for a grown man. He makes the characters in Saturday Night Fever seem complex, multidimensional.

What the movie needs is a good train wreck, whether kinetic (i.e., literal) or metaphorical. (I'd take either.) Joe's life is mysteriously thin (he's as complex, emotionally, as a 10-year-old boy); apparently he has no college loans to pay, no wife or child to feed, nothing to do with his time but hang out at the station all day. Olivia's life is full of pathos, but it's latent, rarely overt. Who are these people? Where are the raging crises in their lives? Olivia lost her son two full years ago; it's in the past; her husband is not the kind of husband any sane woman would want to reconcile with. Where's the tension? There isn't any. I'm sorry.

The main character's arc takes him from bitter and antisocial to less bitter and quasi-social (but still without a love life). That's hardly a satisfying journey.

How to fix this mess? First, make all three main characters' lives train wrecks. Not only that, actually have Joe hang his head at one point and call his life a train wreck so that Fin (the locomotive-history uber-nerd and consummate train-lover) can say: "Please don't ever say that in my presence."

Joe: "What? What'd I say? You mean . . . train wreck??"

Fin: "Please. It's . . . repugnant."

Joe (whose first language is Spanish) gives a no-comprende shrug.

"Re-pug-nant. It means repulsive. Extremely distressing."

This sets up "train wreck" as a metaphor that can be used throughout the movie, while also potentially setting up a funny moment some time later on, when Olivia can slip "train wreck" into conversation (innocently), whereupon both Joe and Fin stare at her and simultaneously say: "Don't ever say that." (Then Joe, on his own: "It's repugnant.")

Writer-director McCarthy took pains to show a scene in which the local-store cashier/owner whips her cell phone out to take a picture of Fin while he's walking around in the store (because apparently, this 50-year-old woman has never seen a dwarf before, in her entire life). Okay, we get it, people treat dwarves like freaks. Unfortunately, McCarthy misses a great opportunity to lend resonance to the store scene later on, when Fin, in a drunken rage, stands on a bar stool in a crowded saloon and yells at people to "Go ahead, look at me." What he should, of course, have done is yell: "Get your camera out, okay? Take a goddam picture." At first, no one moves, but Fin (in my rewrite; if I were script-doctoring this thing) shames the crowd into actually getting their cell phones out. He forces them to take actual pictures of him.

That's not all. Bear in mind, there's a hugely important redemption scene near the end of the movie when Fin, glad to be alive after a near-death experience, finds the nerve to stand in front of an elementary-school class (one kid asks how tall he is) to give a talk about trains. The barroom scene could have given the classroom scene a bit of much-needed resonance if it (the bar scene) had ended with Fin (duly photographed by the shamed saloon crowd) stepping down from the bar stool and saying (angrily, of course) "Thank you. Class dismissed . . ." as he storms out of the bar. Later on, during the classroom scene, we could have Fin allow a local newspaper reporter (newspapers being a symbol, incidentally, for well-past-their-glory-days 19th-century technology, like trains) to take a picture of him with kids gathered around him. The next day, Joe, Olivia, and Fin (or any combination of two of them) could be looking at the picture in the morning paper, commenting positively on it, etc.

Note: The camera is a potentially powerful metaphor in any movie; it's the physical incarnation of voyeurism (which in turn is a powerful motif in cinema).

Fin's closeness with Olivia could have been better exploited. They could have cuddled/rubbed faces, on the bed, fully clothed; then CUT TO an outdoor scene (continuous, night) looking at the bedroom window from outside; we see the light go out (suggesting that more may have then happened on the bed). But we FADE TO a morning indoor scene where we see the two spooning, still fully clothed, atop the still-undisturbed bed, Fin looking like a pearl inside an oyster with Olivia holding him from behind.

I can think of a lot of seemingly little (but potentially important in the aggregate) fluorishes that would have made us care more about the characters (without resorting to the cheap tactic of making them have sex with each other)—quite possibly making for a more satisfying (for me, anyway) film experience. With a little work, The Station Agent could have been even better than it is already. That's not to take credit away from Thomas McCarthy, however. Few people these days can shoot an award-winning, highly profitable (well over $8 million gross) drama for under half a million dollars. That's magic of a pretty high order. Far be it for me to suggest otherwise.

reade more...

What kind of story is it? The logline is suitably quirky: Two loners (Joe and Olivia) try to befriend an antisocial dwarf (Finbar McBride, sensitively played by Peter Dinklage) who has inherited an abandoned train station in Newfoundland, New Jersey.

|

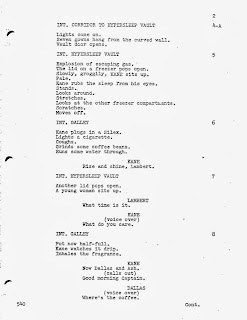

| Joe, Olivia, and Fin watch a movie in The Station Agent. |

While walking to town, Finbar almost gets struck by a swerving Jeep; he thus meets Olivia Harris (played by Patricia Clarkson), a thirty-something woman who lost her only child in a playground accident two years ago and is now separated from her husband.

For a while, it seems as if Fin and Olivia will hit it off and become An Item, but they never do. Instead, she wants to reconcile with her husband (but finds out much later that he's already impregnated his girlfriend). Fin also meets a young librarian, and has a tender moment with her; but alas, she's pregnant by her redneck boyfriend, and she goes back to him (or disappears from the film, at least).

There's a bit of bonding between Fin and Joe, but frankly the Joe character is mostly an irritation (to Fin and the moviegoer) and only barely attains "true friend" status at the end of the story. He's good-natured; you want to like him; but he's extraordinarily immature for a grown man. He makes the characters in Saturday Night Fever seem complex, multidimensional.

What the movie needs is a good train wreck, whether kinetic (i.e., literal) or metaphorical. (I'd take either.) Joe's life is mysteriously thin (he's as complex, emotionally, as a 10-year-old boy); apparently he has no college loans to pay, no wife or child to feed, nothing to do with his time but hang out at the station all day. Olivia's life is full of pathos, but it's latent, rarely overt. Who are these people? Where are the raging crises in their lives? Olivia lost her son two full years ago; it's in the past; her husband is not the kind of husband any sane woman would want to reconcile with. Where's the tension? There isn't any. I'm sorry.

The main character's arc takes him from bitter and antisocial to less bitter and quasi-social (but still without a love life). That's hardly a satisfying journey.

How to fix this mess? First, make all three main characters' lives train wrecks. Not only that, actually have Joe hang his head at one point and call his life a train wreck so that Fin (the locomotive-history uber-nerd and consummate train-lover) can say: "Please don't ever say that in my presence."

Joe: "What? What'd I say? You mean . . . train wreck??"

Fin: "Please. It's . . . repugnant."

Joe (whose first language is Spanish) gives a no-comprende shrug.

"Re-pug-nant. It means repulsive. Extremely distressing."

This sets up "train wreck" as a metaphor that can be used throughout the movie, while also potentially setting up a funny moment some time later on, when Olivia can slip "train wreck" into conversation (innocently), whereupon both Joe and Fin stare at her and simultaneously say: "Don't ever say that." (Then Joe, on his own: "It's repugnant.")

Writer-director McCarthy took pains to show a scene in which the local-store cashier/owner whips her cell phone out to take a picture of Fin while he's walking around in the store (because apparently, this 50-year-old woman has never seen a dwarf before, in her entire life). Okay, we get it, people treat dwarves like freaks. Unfortunately, McCarthy misses a great opportunity to lend resonance to the store scene later on, when Fin, in a drunken rage, stands on a bar stool in a crowded saloon and yells at people to "Go ahead, look at me." What he should, of course, have done is yell: "Get your camera out, okay? Take a goddam picture." At first, no one moves, but Fin (in my rewrite; if I were script-doctoring this thing) shames the crowd into actually getting their cell phones out. He forces them to take actual pictures of him.

That's not all. Bear in mind, there's a hugely important redemption scene near the end of the movie when Fin, glad to be alive after a near-death experience, finds the nerve to stand in front of an elementary-school class (one kid asks how tall he is) to give a talk about trains. The barroom scene could have given the classroom scene a bit of much-needed resonance if it (the bar scene) had ended with Fin (duly photographed by the shamed saloon crowd) stepping down from the bar stool and saying (angrily, of course) "Thank you. Class dismissed . . ." as he storms out of the bar. Later on, during the classroom scene, we could have Fin allow a local newspaper reporter (newspapers being a symbol, incidentally, for well-past-their-glory-days 19th-century technology, like trains) to take a picture of him with kids gathered around him. The next day, Joe, Olivia, and Fin (or any combination of two of them) could be looking at the picture in the morning paper, commenting positively on it, etc.

Note: The camera is a potentially powerful metaphor in any movie; it's the physical incarnation of voyeurism (which in turn is a powerful motif in cinema).

Fin's closeness with Olivia could have been better exploited. They could have cuddled/rubbed faces, on the bed, fully clothed; then CUT TO an outdoor scene (continuous, night) looking at the bedroom window from outside; we see the light go out (suggesting that more may have then happened on the bed). But we FADE TO a morning indoor scene where we see the two spooning, still fully clothed, atop the still-undisturbed bed, Fin looking like a pearl inside an oyster with Olivia holding him from behind.

I can think of a lot of seemingly little (but potentially important in the aggregate) fluorishes that would have made us care more about the characters (without resorting to the cheap tactic of making them have sex with each other)—quite possibly making for a more satisfying (for me, anyway) film experience. With a little work, The Station Agent could have been even better than it is already. That's not to take credit away from Thomas McCarthy, however. Few people these days can shoot an award-winning, highly profitable (well over $8 million gross) drama for under half a million dollars. That's magic of a pretty high order. Far be it for me to suggest otherwise.